Findings at Machu Picchu

It was still misty when we entered the site of Machu Picchu. The only real indication that there might be something different, around us was the sudden absence of foliage, which had given way to orderly terraces.

What we couldn’t see was the arching complex of building and walls, walkways and aqueducts. It wasn’t until we walked out to the edge of a giant rock pulled, out the binoculars, and peered down into the mist, that the familiar shapes, filed in our brains from the pages of textbooks and travel programs, began to emerge.

While the mist thinned under the rising sun, we explored the upper terraces.

The irregular rocks were fitted expertly into each other, forming tall, solid terrace walls. The only rocks protruding from the sides were there by design – steps to climb from one level to the next. The grasses were short and thick, and scattered with piles of smooth black pellets, evidence of the llamas that inhabit the ancient site.

Before entering the lower site, we checked our packs, and looked for Kelly, our fellow-traveler who had stayed behind in Cuzco while LeAnna and I hiked the trail. We’d planned ahead of time to meet at the main gate. But we were late, and Kelly was nowhere to be seen. After about 20 minutes, we checked with Odon, who called the tour office to check for messages. Then we called the hotel. Nothing. I even tried to see if we could cross reference ticket numbers to determine if she’d already entered the site. No luck.

I loaded a small pack for the 6 hours we’d spend inside the site, making sure to pack my binoculars. They might be our only hope of finding that day Kelly.  Then we reentered Machu Picchu, the sun beginning to stream through the clouds.

The site was massive. Odon served as our guide for the first two hours. He took us through the noble houses, where the stones were smoothed from the rough-hewn blocks that made up the majority of the buildings, and then into the sun temple, where the stones were polished even further, indicating the deeply sacred nature of the space.

One theory about Machu Picchu is that it was the city of the Inka. Like, THE Inka. The dude in charge of the empire. That this place was where the most sacred priests lived, and where the family of the Inka lived. Nobody really knows, but there are a lot of temples there. There was the Sun Temple, climbing organically out of a large rock base in the middle of the site.

The temple of the Condor, where blood would be fed to the condor through the little hole at its beak that leads to an underground cavern (the stomach), which would hold the rest of the offering.

The main temple,

with it’s sacred sundial (which was damaged during the making of a car commercial – for real).

Machu Picchu is home to a number of other sacred rocks. Those that look like the actual sacred mountains that surround them.

The sacred rock is in the lower right hand corner, mirroring the shape of the mountain in the middle.

Rocks that, when lain upon transfer the energy of the earth.

And those that, by their energetic makeup are believed to impart power to individuals who touch them.

One such rock sits at the base of the trail to Huayna Picchu, the tall spire of a mountain at the back of the site.

The stone, which shows visible sign of centuries of human hands touching its surface, is part of a resting area, a meditative retreat believed to help prepare travelers for the difficult hike to the top of the mountain, and the Temple of the Moon.

Odon warned us against touching the stone. “You have to have the right makeup – the right energy.â€Â He told us that the high quartz content of the stone could make you feel sick if you weren’t ready for it.

Nobody in our group saw the Temple of the Moon, not because we didn’t want to, but because the government has greatly restricted the number of people who can climb the trail each day. In order to get a ticket, you have to be at the Machu Picchu gates around 5:30am.

So we were relegated to the lower site, with its llamas and terraces.

At one point, one of the llamas, who roam free throughout the site, stepped across the path, separating our group for a good 5 minutes, before it decided to move along.

One of the women in the group called to those of us nearest to just move past it. The guy next to me looked over and said, “You go ahead. I raise llamas. I have no intention of getting kicked in the head.â€Â So we waited until we were allowed to move to our next stop.

While we walked, we were constantly scanning the site for Kelly. She was there somewhere, in a straw cowboy hat, and a red backpack. I was quite certain we could find her, if we kept the binoculars handy, and kept a steady eye out for her. But the pure vastness of the place, with its sharp turns and steep angles made it difficult to see much.

To make matters slightly more challenging, Odon informed us that, very soon, 10,000 new visitors would be arriving, making it virtually impossible to find anyone.

Just as we were winding down our visit, deciding that we’d be more likely to find Kelly in the tiny streets of Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of the mountain, I spotted her through my binoculars.

“No way. She’s there!â€Â Climbing the steps to the main temple, Kelly’s hat and backpack made her stick out. LeAnna and I ran through the site, (until we were stopped by guards) catching Kelly’s attention, ugly-American style, by jumping and waiving from below the temple.

“Where were you? Sorry we were late! We’ve been searching for you.â€

“Didn’t you get my note?â€Â Kelly looked at us a little baffled. “I left it for you at the bag check.â€

Of course she did. It was the thing that made the most sense. And the one thing we hadn’t checked. Brilliant.

As it turned out, Kelly, unable to make the three-day trek with us, had scored one of the coveted tickets to the top of Huayna Picchu and the Temple of the Moon.

We compared notes on what parts of the site we had seen, and made a plan that would take us through the rest and get us on a bus to the town in time for a final meal with our group.

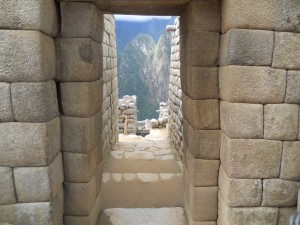

Our last, winding walk through Machu Picchu was hauntingly memorable. We found beautiful, framed views,

ancient rooms,

and amazingly preserved details.

Even so, Machu Picchu, with its temples and stones, revealed nothing of its secrets to us. None of us became shamans. None of us had life-altering visions. But we did find each other. Amid the mysteries, in a spot of sunlight, we saw each other, before the mist returned to blanket Machu Picchu once more.

February 4, 2011 Comments Off on Findings at Machu Picchu

Porters

We woke at 3:30 to the sound of our porters, “knocking” on the tent. “Coca tea, coca tea…” Handed through the rain fly and sleepily consumed, the tea woke us and prepared us for the climb ahead.

An hour later, we were running down the ancient Inka Trail, racing the sun on its path to the horizon. Our goal was the Sun Gate, as we ran in the dark, 30lb pack, headlamp, trekking poles and a 1,000 foot drop to one side.

“I think I need more adventure racing in my life,” I thought to myself, a grin and a cackle rising to my mouth.

We’d spent the day before running down the 2,000+ steps from Deadwoman’s Pass. LeAnna and I were convinced now that it was easier than walking. From a perch high in the Andes, looking out over the cloud forest, we surveyed what lay ahead of us.

We’d climbed to a point that was undeniably sacred. The mist washed over the place, muffling voices, disorienting, transporting.

We stayed a short time, climbing as high as we could. We sat in silence, taking in the peaks that surrounded us; breathing in the strength of the ancient mountains. When we departed, it was quietly, leaving a small offering.

Once off the peak, we found ourselves in another world. Our surroundings changed from the high-steppe of the cloud forest to the damp, lush overgrowth of the rain forest, marked abruptly as the path dipped below the canopy before us.

Always we were walking down. Down the sloping path, down the stone steps, down, down, down we trotted, undoing the work we’d done the day before.

We stepped aside when we heard the padding of feet, and “porters†gently called to us.

In their sandals made of recycled tires, showing dry, calloused heels and blackened nails, the porters had an amazing mastery of the trail. Muscled calves bulged under the weight of impossible loads: canvas sacks fitted with shoulder straps and stacked high with tents and camp chairs, gas tanks and burners, cookware and tarps. Most bags were as tall as their porters, and always wider. The men often ran with their hands behind them, supporting the underside of their packs, waist belts ignored and hanging uselessly.

On this third day of our trek, we were feeling good. We looked at each other and, instead of hanging back like we had for two days, we fell in line behind a group of the small, weathered men.

It’s a marvelous thing to find yourself traveling with a companion who shares your sensibilities. Without a word, we decided to see if we could hang with these porters. And so we ran, indelicately down the path.

It must have startled at least one of the porters. Hearing our scuffling, he stood aside for us to pass, a bemused look on his face.

“No, no!†We waved our arms at him, beckoning him on in front of us. It was one thing to run behind the porters, but quite another to run in front of them. So we stayed behind, watching as they slid around hairpin turns and cut off the trail to take nearly invisible shortcuts.

For two hours, we ran. We kept the porters within earshot nearly the entire time. Only in the last 10 minutes before camp were we passed by others. We felt good. We celebrated as we came around the corner and saw the green and yellow of our porters’ food tent, and the surprised looks on their faces.

The surprise turned to smiles as they clapped for us. And then they set to work. We were indeed a surprise. The sleeping tents weren’t yet set, and the food was far from ready. These guys had only just arrived before we had. Guilt joined our emotions as we watched them scramble to set camp – something they clearly hadn’t planned on having to do for a while.

We slept early and hard that night, knowing the ungodly hour at which we’d be expected to rise. But not before we’d gone through an elaborate ceremony designed specifically to allow us to tip our new friends. Francisco, their spokesman and shaman spoke to us, calling us “brother†and “sister†and talking of the connection that all of us share.

For our part, we thanked them in Spanish, as well as we could. I thanked them for everything, “todo,†which was heard as “toro,†or bull. One of many misunderstandings…and then we tipped each of them according to their job description from a pool of money we had all gathered together – an attempt to say thank you for the backbreaking work they did, and the cultural heritage they shared with us.

* * *

Day 4 had started at 3:30 a.m. for a couple of reasons. We had to hike half a mile up the trail to wait at the last checkpoint with the hundreds of other trekkers who wanted to make the Sun Gate before sunrise. It meant sitting at the checkpoint for an hour and a half, but it also meant having relatively few people in front of us on the trail.

The other reason was to allow the porters to run the 90 minutes down to their 6 a.m. train that would take them back home. They would be leaving us to go on to Machu Picchu alone. I asked Odon how many of the porters had ever seen the sacred site.

“None of them.â€Â Our guide seemed amused by the question. It cost money to see the site, and the porters had to catch the train back far too early to allow them to venture on. Odon had spent years as a porter, running the trail 4 times a week. After years studying “hospitality services,†he was now a guide. He wore hiking boots and carried only a small pack with his personal items. He would be entering Machu Picchu as our guide. The other Peruvians would be running with all of their might to catch a train so that they could prepare for the next day’s brutal return to the trail.

It’s a humbling thing to realize your privilege. To sit in the mud, having paid for the opportunity to do so. Waiting to see the cultural heritage of a people that carried my food so that I could see something that they never would – the sites created by their ancestors.

Dressed in the freshest clothes we had, we marinated in our adrenaline, willing the checkpoint to open. When it did, we found ourselves in an adventure park setting. Something between Disneyland and Jurassic Park surrounded us. One misstep could seriously send us hurtling down hundreds of feet of drop-off.

There were only a couple dozen trekkers in front of us. LeAnna and I had angled to the front of our group, eager to continue our running of the trail. But this section was narrow, and didn’t provide much opportunity for passing. Eventually, we made it to the front, moving past people who stopped to tie shoes or drink water. We were possessed.

Only once did we stop – to remove layers rendered unnecessary by our running. Neither of us wanted to find ourselves sweating and chilled in the early morning cold. While we stripped with lightning speed, one small group of two passed us. We swore under our breath and redoubled our efforts. We knew we were close, but we didn’t realize just how close. The Sun Gate was at the top of the “ladder,†a series of steep steps.

As soon as we resumed our jog, we hit them.

“Steep†didn’t quite describe them. We climbed, hands and feet, up the nearly vertical rocks. I struggled, my pack weighing heavy, as I heard heavy breathing behind me. I toppled backward once, reaching out and grasping at the rocks, saving myself and the people behind me. LeAnna and I built a wall, climbing side-by-side so that we would reach the top without being passed again. (Like I said, possessed.)

And then we were there. At the Sun Gate. With almost nobody around, we surveyed the view. It was cloudy. There would be no sunrise for us. But it made no real difference. We stood at the top and looked through the mist at the bits and pieces of landscape that were revealed.

The rest of our group materialized, and we posed for our second mandatory group shot.

One more hike, and we’d be at our destination – a place that had eluded Spanish conquests. A place that is still not completely understood. A place secret, and sacred and hidden.

The trail led on, past sacred rocks and through parts that had been washed out by mudslides.

The closer we got, the reasons it had remained secret became more and more clear.

The enormous site of Machu Picchu lay hidden in the mist. It was right in front of us, and we had almost no indication that it existed.

“Secret and sacred,†Odon had intoned. As we watched the swirling mists, we began to see.

November 24, 2010 1 Comment