Porters

We woke at 3:30 to the sound of our porters, “knocking” on the tent. “Coca tea, coca tea…” Handed through the rain fly and sleepily consumed, the tea woke us and prepared us for the climb ahead.

An hour later, we were running down the ancient Inka Trail, racing the sun on its path to the horizon. Our goal was the Sun Gate, as we ran in the dark, 30lb pack, headlamp, trekking poles and a 1,000 foot drop to one side.

“I think I need more adventure racing in my life,” I thought to myself, a grin and a cackle rising to my mouth.

We’d spent the day before running down the 2,000+ steps from Deadwoman’s Pass. LeAnna and I were convinced now that it was easier than walking. From a perch high in the Andes, looking out over the cloud forest, we surveyed what lay ahead of us.

We’d climbed to a point that was undeniably sacred. The mist washed over the place, muffling voices, disorienting, transporting.

We stayed a short time, climbing as high as we could. We sat in silence, taking in the peaks that surrounded us; breathing in the strength of the ancient mountains. When we departed, it was quietly, leaving a small offering.

Once off the peak, we found ourselves in another world. Our surroundings changed from the high-steppe of the cloud forest to the damp, lush overgrowth of the rain forest, marked abruptly as the path dipped below the canopy before us.

Always we were walking down. Down the sloping path, down the stone steps, down, down, down we trotted, undoing the work we’d done the day before.

We stepped aside when we heard the padding of feet, and “porters†gently called to us.

In their sandals made of recycled tires, showing dry, calloused heels and blackened nails, the porters had an amazing mastery of the trail. Muscled calves bulged under the weight of impossible loads: canvas sacks fitted with shoulder straps and stacked high with tents and camp chairs, gas tanks and burners, cookware and tarps. Most bags were as tall as their porters, and always wider. The men often ran with their hands behind them, supporting the underside of their packs, waist belts ignored and hanging uselessly.

On this third day of our trek, we were feeling good. We looked at each other and, instead of hanging back like we had for two days, we fell in line behind a group of the small, weathered men.

It’s a marvelous thing to find yourself traveling with a companion who shares your sensibilities. Without a word, we decided to see if we could hang with these porters. And so we ran, indelicately down the path.

It must have startled at least one of the porters. Hearing our scuffling, he stood aside for us to pass, a bemused look on his face.

“No, no!†We waved our arms at him, beckoning him on in front of us. It was one thing to run behind the porters, but quite another to run in front of them. So we stayed behind, watching as they slid around hairpin turns and cut off the trail to take nearly invisible shortcuts.

For two hours, we ran. We kept the porters within earshot nearly the entire time. Only in the last 10 minutes before camp were we passed by others. We felt good. We celebrated as we came around the corner and saw the green and yellow of our porters’ food tent, and the surprised looks on their faces.

The surprise turned to smiles as they clapped for us. And then they set to work. We were indeed a surprise. The sleeping tents weren’t yet set, and the food was far from ready. These guys had only just arrived before we had. Guilt joined our emotions as we watched them scramble to set camp – something they clearly hadn’t planned on having to do for a while.

We slept early and hard that night, knowing the ungodly hour at which we’d be expected to rise. But not before we’d gone through an elaborate ceremony designed specifically to allow us to tip our new friends. Francisco, their spokesman and shaman spoke to us, calling us “brother†and “sister†and talking of the connection that all of us share.

For our part, we thanked them in Spanish, as well as we could. I thanked them for everything, “todo,†which was heard as “toro,†or bull. One of many misunderstandings…and then we tipped each of them according to their job description from a pool of money we had all gathered together – an attempt to say thank you for the backbreaking work they did, and the cultural heritage they shared with us.

* * *

Day 4 had started at 3:30 a.m. for a couple of reasons. We had to hike half a mile up the trail to wait at the last checkpoint with the hundreds of other trekkers who wanted to make the Sun Gate before sunrise. It meant sitting at the checkpoint for an hour and a half, but it also meant having relatively few people in front of us on the trail.

The other reason was to allow the porters to run the 90 minutes down to their 6 a.m. train that would take them back home. They would be leaving us to go on to Machu Picchu alone. I asked Odon how many of the porters had ever seen the sacred site.

“None of them.â€Â Our guide seemed amused by the question. It cost money to see the site, and the porters had to catch the train back far too early to allow them to venture on. Odon had spent years as a porter, running the trail 4 times a week. After years studying “hospitality services,†he was now a guide. He wore hiking boots and carried only a small pack with his personal items. He would be entering Machu Picchu as our guide. The other Peruvians would be running with all of their might to catch a train so that they could prepare for the next day’s brutal return to the trail.

It’s a humbling thing to realize your privilege. To sit in the mud, having paid for the opportunity to do so. Waiting to see the cultural heritage of a people that carried my food so that I could see something that they never would – the sites created by their ancestors.

Dressed in the freshest clothes we had, we marinated in our adrenaline, willing the checkpoint to open. When it did, we found ourselves in an adventure park setting. Something between Disneyland and Jurassic Park surrounded us. One misstep could seriously send us hurtling down hundreds of feet of drop-off.

There were only a couple dozen trekkers in front of us. LeAnna and I had angled to the front of our group, eager to continue our running of the trail. But this section was narrow, and didn’t provide much opportunity for passing. Eventually, we made it to the front, moving past people who stopped to tie shoes or drink water. We were possessed.

Only once did we stop – to remove layers rendered unnecessary by our running. Neither of us wanted to find ourselves sweating and chilled in the early morning cold. While we stripped with lightning speed, one small group of two passed us. We swore under our breath and redoubled our efforts. We knew we were close, but we didn’t realize just how close. The Sun Gate was at the top of the “ladder,†a series of steep steps.

As soon as we resumed our jog, we hit them.

“Steep†didn’t quite describe them. We climbed, hands and feet, up the nearly vertical rocks. I struggled, my pack weighing heavy, as I heard heavy breathing behind me. I toppled backward once, reaching out and grasping at the rocks, saving myself and the people behind me. LeAnna and I built a wall, climbing side-by-side so that we would reach the top without being passed again. (Like I said, possessed.)

And then we were there. At the Sun Gate. With almost nobody around, we surveyed the view. It was cloudy. There would be no sunrise for us. But it made no real difference. We stood at the top and looked through the mist at the bits and pieces of landscape that were revealed.

The rest of our group materialized, and we posed for our second mandatory group shot.

One more hike, and we’d be at our destination – a place that had eluded Spanish conquests. A place that is still not completely understood. A place secret, and sacred and hidden.

The trail led on, past sacred rocks and through parts that had been washed out by mudslides.

The closer we got, the reasons it had remained secret became more and more clear.

The enormous site of Machu Picchu lay hidden in the mist. It was right in front of us, and we had almost no indication that it existed.

“Secret and sacred,†Odon had intoned. As we watched the swirling mists, we began to see.

November 24, 2010 1 Comment

The pass

Odon wanted us up and out of the first night’s camp site by 7:30AM. Most of us were up, mostly on time, the porters’ gentle tapping on our tents bringing us back from our exhausted sleep to our location on the side of the trail.

The chickens were scratching at the grass around the tents, and the mist was beginning to burn off. We all tumbled roughly out of our bags and wandered in small groups to the bathrooms, some hacking; some rubbing our eyes sleepily. Then we dressed and pulled our packs out of the tents, redistributing weight, and determining what would be carried by our hired porters. Almost the second our tents were free of gear, the porters had them broken down and packed away. Over the course of the trek we would be witness to the hyper-efficiency that had them simultaneously preparing meals, washing dishes and breaking down or setting camp. Even at our best, we were a half-step behind – simply hanging on enough to get ourselves into the meal tent.

The orange, plastic wash basins placed at the entrance to the meal tent before each meal, were filled with warm water for us to clean our hands and faces. Along with a good tooth-brushing, they provided a comfort, a sense of normalcy as we pawed our way through the mountains.

This morning, we were scheduled to officially meet the porters. Before we all shouldered our loads, we stood across from each other and shared names, professions, ages, and hometowns.

Francisco, the leader of the porters stepped forward. A man of medium-height with a mesmerizing smile and sparkly eyes, he was the representative of the group. He was also the shaman. He would make the offerings that kept our group safe on the trail. He welcomed us and turned to the other porters to introduce themselves. Along with their jobs, they told us their ages. Francisco, at 35, was the youngest. The eldest was 62. He was a tiny, wiry man who we had seen on the trail with a noticeably larger load than the others. When Odon translated this man’s introduction, he explained that the eldest of the group always carries more weight than the others, in order to show that he is still able to shoulder his load.

Then it was our turn. I tried my intro in Spanish, looking to Odon for the word for “writer,†and received approving smiles and nods. The porters spoke the local, ancient language, but had more Spanish than English. My effort was noticed. A lot. Francisco interrupted to ask Odon if I was married, hiding his grinning face behind one of the other giggling porters.

The introductions were completed with a cultural exchange. The porters taught each of us a phrase in their language. Things like, “How are you?†and “Don’t get tired,†were repeated as we tried desperately to memorize them.

“Odon, how do you say thank you?â€Â I wanted to be able to address our porters in their own language. Odon looked at us, and gave us the answer. It was something that sounded like “sul pie key.â€Â And then he explained that we should add “wai key†to the end, making the phrase, “thank you, brother.â€

“You see, there is no word for ‘friend.’ Everyone is a brother or a sister.â€Â Beautiful. We all practiced, committing the phrase to our deepest memories so that it wouldn’t escape as we climbed to 14,000 feet.

And that’s where we were headed: Dead Woman’s Pass at just over 14,000 feet above sea level.

“We’re walking alone today. Everyone go at your own pace.â€Â Odon had special instructions for this part of the trek. “You will get tired. It’s okay to stop. Stop as often as you’d like. Walk for 10 minutes and then stop for 10. That’s fine. But don’t sit down. Never lie down.† His face was serious. “If you do that, you won’t be able to get back up. You won’t make it to the top and we’ll have to take you back down. There’s some medical reason. I don’t know, but you need to not stop for too long. Don’t wait at the top for anyone. Just take you pictures and start down the other side.â€

This was more intense than I’d expected. He was talking about blood pooling. It made sense. We’d be a lot higher than our bodies were used to. Blood wouldn’t be pumping as well. Oxygen deprivation was a serious thing.

And with Odon’s words ringing in our ears, we struck out, through the little village, along the trail that would take us to the pass.

We were about an hour behind Odon’s schedule. He seemed anxious to get us moving. Even with lighter loads, this leg would be the most taxing of the week. We’d been told we’d hiking for 7 or 8 hours. Somehow, I thought this was a hyper-inflated number designed to scare us a little. It was not.

We hiked. And hiked. And hiked. And then we hiked some more, kept company by the imposing mountains, and ever climbing trail.

It was three hours before we had any view of the pass. Three hours of walking up the trail, climbing up the steps that seemed too large for small Inkans, three hours of stopping to breathe. When we finally saw the pass, and the line of people, like cliché ants winding their way closer, we all stopped. A bunch of us were heading up at the same pace, leapfrogging each other as we stopped to take pictures, and to suck down water from the tubes that ran over our shoulders from the bladders in our packs. The act of biting the plastic, sucking and swallowing was almost too much to do while hiking. It left me nearly breathless, struggling to catch wind while I scrambled along the path.

I gasped a little when people took off their packs and sat down. I could hear Odon. I could see the blood pooling in their legs. “Do you think we should be sitting?â€

“It’s just for a minute. We’ll be fine.â€

I unclipped my pack and leaned back against the earth wall that was the side of the trail. It was the most I was willing to risk. We could see the top, and that felt good, but we were still another hour away from the last checkpoint, according to Odon. From there it would be another hour or two. I was pretty sure, by this point, that he wasn’t trying to scare us with the 7 or 8 hour number, and probably not with the blood pooling, either.

From then on, we walked for no more than 15 minutes between breaks. The air was thin. It was beginning to get cooler. And the novelty of the trail was wearing off.

The final checkpoint before the pass was in a field, high in the mountains. It sat opposite a lake. A black glass pool, rigid and vacant. The light was bright and the atmosphere strange. Some trekking companies had set their meal tents near the checkpoint. Porters rushed up and down the trail, and burners boiled water in large pots close to the ground.

I took advantage of the bathrooms here. With my pack set aside and my toilet paper in hand, I jogged into camp , past Australian trekkers on their way back from the toilets. “How are they?â€Â I tossed the obligatory question at them as I passed.  “Not bad, actually.â€Â The woman who responded was nodding in an approving way.

The mood in the camp was a mixture of tired and excited. We were all close. The trail runs one way, so everyone there was headed to the pass, whether under their own steam, or on the backs of the porters.

Once back on the trail, we looked up at the pass. It was right there. Right there in front of us. It looked so very close.

But Odon said it would take another hour and a half to get there. And it did. We were part of a line of trekkers. Most of them were traveling without packs, but moving quite as slowly as we were. It felt good to be keeping pace with them. Good emotionally, but physically I was panting open-mouthed, trying to get as much oxygen to my brain as possible.

Every so often, we’d hear “porter!†and we’d shuffle to the side of the little trail to make room for the men who were running, yes running, up the mountain with unfathomable loads on their backs.

Almost all of them ran in sandals. Shoes made of old tires. The newer porters had blisters. Sometimes there was blood, and rarely it was wrapped. The older porters just had amazing calluses, whether from running the trails, or from working the fields. Most of them were farmers. They would run past us, holding the packs to their backs and disappear over the saddle of the mountain.

We knew we had reached the top, when we found a pile of backpacks and saw a large group of people sitting. The pass wasn’t the tallest peak. It was the way between the tallest peaks. Some people were climbing higher on either side, looking for a better view. Many others were sitting down, taking in the view, and hydrating for the downhill portion of the day.

It’s great when you find yourself traveling with someone who thinks the same way you do. Our moment at the top of the pass was one of those times. LeAnna and I looked at each other and silently agreed that we weren’t going to do what everyone else was doing.

We took our pictures and then gathered our packs and hurled ourselves down the backside of the mountain. This was the perfect opportunity to get in front of the chattering, coughing, packless masses that had beaten us to the top.

We really did hurl ourselves. Odon had mentioned that the porters run downhill, not only because they need to beat the rest of the trekkers into camp, but because it’s easier on your body to run. I’d known this to a lesser extent from running cross country in high school. But the idea of running with 30 lbs on my back was a little daunting. By this time, we trusted Odon. So we decided to give it a try. Down a gazillion rough-hewn rock steps in the middle of the Andes.

He was right. (Of course he was.) Using our walking sticks to stabilize, it was much easier. We ran, skipped, and bounced down the steps. I swear we saw almost nobody the entire 2 and a half hours we hiked down. It was blissful. The mist that was overtaking the pass was absent on the backside. The trail was open and exposed, lined with low scrub brush, which allowed us to see down into the valley where we would be making camp for the night, as well as the trail we would be taking the next day.

This really was one of the best parts of the trek. LeAnna and I looked around constantly, grinning and giggling. We were running the Inka Trail. We reached our camp before the rest of our group, and before most of the others on the trail. This meant a couple of things: our pick of tents for the night,

and food served to the two of us in a quiet tent.

But most importantly, it meant first crack at the bathrooms.

This might sound unimportant, but when 20 women are using one toilet in the middle of the mountains, it’s critical.

We napped in our tent, while the others filed into camp. They’d waited for each other in the thin air. They ate, and we drifted in and out of consciousness. The incredible view of the clouds below us was the best entertainment we could ask for.

Soon enough, we were eating again. First we had “happy hour,†which consisted of popcorn, pizza, and language lessons.  Our porter, Francisco, was the only one willing to participate. We sat across from each other while our cohorts looked on. I’d point to something, say the English name, and then he’d repeat it and give me the counterpart. It took a moment before I realized he was giving me the Spanish. With a little coaxing, he translated the words into Kechua. I tried to repeat and memorize, but the clicks and creaks that came from his mouth weren’t something natural to me.

Happy Hour moved into dinner, and we all tried to stuff as many calories into our tired bodies as possible. It was our third meal in 4 hours, and the amount of food on the table let us know that we were expected to be eating a lot. Day 3 was no joke. We were facing a very long day, with climbs, and a 2,000-step descent.

Stuffed peppers, pasta, chicken legs, soups. Odon watched us closely, asking how we each felt, and calculating how much clean water we would need for the next day. Which would begin at 6AM. Today’s late start meant that Odon would have far less patience the next two mornings. And so as the mountains went dark, we climbed into bed, our bodies grateful and our minds quiet.

October 7, 2010 1 Comment

The other Americans

It was early when we got up. Thankfully, the excitement of the trail pulled us out of bed, and the promise of a good breakfast drew us into the dining area.

It was 4:30. We had 15 minutes to throw down breakfast and get our bags to the front door for our shuttle pick up that would take us to the start of the Inka Trail.

And that was the goal. The Inka Trail. We were signed up for the 4-day trek that would take us some 29 miles through the jungles of Peru to Machu Picchu. Kelly’s foot was acting up, which meant LeAnna and I would be going it alone. Well sort-of alone. We were trekking with a group – the only way to hike the trail after the mudslides earlier in the year.

During our briefing in the trekking office the night before we’d inquired about the others in the group. There were 5. We got visibly excited when our guide told us there were Israelis, Britts and a German. Then he laughed at us. “No, all Americans.â€Â Darn. We liked our countrymen just fine, but it was exciting to think that we might have some kind of a cultural exchange with the other trekkers.

We climbed into the van at 4:45. It was already filled with our new companions and a couple of our porters, short, dark, smiling men wearing woolly, knit hats with ear flaps and tassels.

LeAnna and I crawled across the second row of bench seats and settled ourselves in for a nap. The others talked animatedly about their trip so far, the beeping watch that one of the girls refused to fix, and about the sickness that had ravaged their group. Seriously? Sickness?

LeAnna and I shot sideways glances at each other. The idea of spending 4 days with a sick person wasn’t entirely appealing. The idea of doing it while hiking to 14,000 feet and sleeping in tents was almost too much.

We drove up and out of Cuzco, watching the villages come alive with workers preparing for the day. After a quarter of an hour of tattling along the roads, we pulled over and one of the porters hopped out. The porters would be carrying our food, and non-personal gear. This guy returned with a propane tank the size of the tank for a barbecue. It weighed 35 lbs according to our guide, Odon. We felt bad for whoever would be hauling that thing. Little did we know…

The terrain was serious. Steep mountains reminded me of the cliffs I’d seen in Japanese scrolls, and the towns nestled in the valleys buzzed with life, streams of smoke rising from rooftops.

We dozed off and on, LeAnna, our porters, and the other Americans. The small, dark man next to me put his chin to his chest and drifted off, our arms touching gently in the crowded van. Between unconsciousness, I opened my eyes enough to get snapshots of my surroundings. The tall mountains, the deep rivers, the bull rings, standing out like red and white targets.

Our arrival into Ollantaytambo, the starting-place for the trek, was unceremonious. We pulled our little van alongside the enormous tour busses and stepped out into a crowd of swarming, buzzing locals selling their wares. Emergency ponchos, energy bars, rubber tips for hiking poles (I actually bought some of these), everything we could possibly need was pressed onto us as we made our way up the stone streets. We were allotted 45 minutes to shop, use the bathroom, and eat.

LeAnna and I walked away from the crowd and tried to take in our surroundings. We were in the mountains. That was for sure. And there were ruins at the far side of the town: deep steps built into the side of the steep slopes.

We barely had time to catalog them as we reeled around. The importance of the elements was clear. Not only were the mountains ever-present, the streets ran with swiftly flowing water channels.

They provided a water-source for every member of the community.

We weren’t especially hungry, but we knew we’d be hiking for something like 8 hours that day, so we decided it was a good idea to eat. We found a funky place, the Living Heart Café, founded by a British woman who wanted to provide education for local children and opportunities for local women. We had quinoa porridge. It was good. Darn good. We scarfed it down, along with a cappuccino (for good measure) and tried to figure out if the other Americans in the restaurant were our trail-mates. It had been so early when we met them that we weren’t sure.

And then we were back at the van for the short ride to the trailhead. There was more talking in the van now, as we drew closer to our next adventure.

At the trailhead, LeAnna and I checked and re-checked gear, discussed our plan for the day, and posed, fresh-faced, for each other’s cameras.

There was much adjusting of packs. When I decided to hike the trail, I decided that, aside from food and tent, I wanted to carry my own gear. It was an issue of pride for me, to prove to myself that I could carry what I needed. I became even more attached to the idea when I found out I was the oldest person on the trek. That’s right, me. At 33, I was the eldest of our group. Insane. So I was hyper-prepared. I had my pack packed tight. I had it on my back , with my trekking poles set. I had coca leaves and tons of water accessible to prevent altitude sickness. I was ready.

When Odon, our guide, called us together, LeAnna and I were first there. We waited as one of the others, in a loud voice, helped his entire posse adjust their packs. We refrained from rolling our eyes, and waited patiently. I noticed how heavy my pack was, and checked that the coca leaves were close by. We were starting the trail at 12,000 feet above sea level.

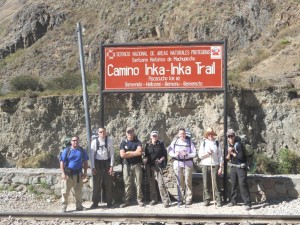

After our final briefing, we headed to the trail, and paused for the obligatory group photo.

Odon patiently worked through all 6 of our cameras that were swinging from his wrist. I considered the blue skies and the gorgeous mountains. And I reached for my coca.

Now, before the trip I’d heard from everyone who had gone, “drink the coca tea.â€Â I’d decided, however, that I didn’t need to be ingesting a substance; that I could do the trek without. That is perhaps true. However, after spending 3 days in Cuzco, I knew what an altitude headache felt like, and I wasn’t interested in having one on the trail with 30 lbs on my back.

So I took the leaves, which looked just like bay leaves, and I crunched them up. Then I stuck them in my cheek. I stuck a lot of these crushed-up leaves in my cheek. If you are or know anyone who is a tobacco chewer, you probably know that this is not the way to chew a leaf. The correct way, as I would later find, is to take the entire, dry leaf, moisten it in your mouth, and then fold it gently into your cheek.

By the time we’d reached the checkpoint 1/8 of a mile in, my mouth was numb.

“My mouth is numb,†I said, turning to LeAnna. “It almost tastes like Novocain.â€

“Um,†she said, looking an even mixture of alarmed and amused, “that’s what they make Novocain out of.â€

My God, she was right. I spit the green bits out as much as I could, but they were still wedged between my teeth. I didn’t really have time to deal with the coca situation, however, as we were almost immediately climbing. We crossed the Urubamba River and headed up.

I swear to you, I thought I might very potentially die. I wondered if I’d have a heart attack, if I’d black out and fall off the side of the cliff, or if my body would simply give up. We were 5 minutes into the trek. It wasn’t good.

I don’t know how, but I managed to muster one last grin as I was gasping for air and trying to settle my thundering heart. I was honestly afraid for my physical wellbeing, and equally afraid to show how much trouble I was having.

But the trail leveled out, and I was able to catch my breath – roughly. I was still a little distressed by the pace that Odon was setting. I was in pretty decent shape, but I hadn’t been training at high altitude, and I hadn’t been hiking for 8 hours a day, nor with a big pack. LeAnna seemed okay, and the others weren’t far behind us. One big voice was booming on, but everyone else seemed to be quieting down. Maybe they were experiencing the same shock I was. I don’t know, I was focusing on breathing.

Twenty minutes in, we hit the first checkpoint. It was a bend in the ancient rock trail where local vendors had tiny stands selling Gatorade and toilet paper. We sat in the shade of an enormous avocado tree. Odon pointed at the fruit that was the size of my hand and told us it was small fruit. “In a month there will be a hundred of them, this big.â€Â He held his hands to indicate something the size of a small cantaloupe.

I looked around at the stray dogs that, even here, were ubiquitous. Â Â A tiny, three-legged dog hobbled around, more at ease than I was.

I chuckled to myself.  Great sign for what was ahead.

We left the checkpoint after a 15 minute water break, Odon in the lead.

All thoughts of a “paved path with handrails†were abruptly shoved from my mind. Whomever had told me that I’d be disappointed at the commercialization of the trail had no idea what they were talking about. For real.

Another half an hour on, we came to our first archeological site. One thing I hadn’t expected from the trip was all of the archeology. I thought we’d hike a long-ass trail and then arrive at Mochu Picchu. The sites that we visited each day were a brilliant surprise.

From this site, we looked down onto a bigger site, and across the river to one of the original Inka trails that connected the great, ancient cities of the Inkan empire.

We spent some time wandering around the site, listening to Odon’s explanation and marveling at the enormity of where we were.

Then we headed on to lunch. We hiked another hour before we saw the green and yellow of the food tent that would serve as a beacon for the next four days, signaling rest and food were near.

Our beautiful porters were responsible for carrying the common gear. The tents and the plates and the food. They literally ran ahead of us with ridiculously-huge packs on their backs and set up for us, preparing beautiful meals. We tossed our packs onto the tarp that was lovingly laid out for us, hurled our bodies onto the packs, and promptly, and collectively fell fast asleep.

I’m not sure if the smell of the food or the porters voices woke us up. We dragged ourselves up from the ground and into the little tent. The food began simply with bits of garlic bread and corn soup. And then it became a huge tray of saffron rice, stuffed avocados, and a cheese pudding.

It was clear that my concern about eating as a vegetarian was unnecessary. Even though they carefully prepared egg dishes for me whenever the others ate meat, I would have been more than fine eating all of the other food that graced the table at every meal.

The meal, like every meal, ended with tea and coca leaves. I was the only one to add the leaves to the hot water. I had no intention of feeling the way I had earlier in the day. I grabbed a banana, and stuffed it down. I also had no intention of running out of steam on the trail.

We had at least another 3 hours left on the trail for the day, and though we could have lain down, each and every one of us, and slept through the night, we had to shoulder our packs and head on. This was the test day. Odon was watching us to see who would be able to make it over the pass, and who would be sent back. This wasn’t a test any of us wanted to fail.

The trail meandered up and down, and we all walked together, more or less. Odon would stop us every so often to wait for those who were taking a little longer, or to sit and talk with a friend along the trail.

Odon was fascinating. He had spent years as a porter. Carrying the packs of other people up and down the trail. Now he hikes the trail once a week. ONCE A WEEK. We did some quick math and figured that he’d hiked the trail something like 500 times. That, my friends is amazing.

The terrain changed a bit from dusty plains to high-steppe. The sky continued to shine a startling blue, and the snow-capped mountains got gradually closer.

Our first-nights camp was in a village. A very small village on the side of the trail. The company had an agreement with locals to camp in what appeared to be their backyard. Chickens, big ones, ran around the tents, looking for handouts as we claimed our sleeping quarters for the night, and admired the view.

After another brief nap, and foray to the bathrooms (the bathrooms on the trip will require an entire and separate post), it was time to eat again. This time it was popcorn, potato soup, alpaca, eggs, and jungle potatoes – an extremely starchy potato that I was sure was filling us with energy for the morning.

Odon let us know that the Porters were monitoring how much we ate. Not only was it more weight off their backs, it was an indication of whether or not we’d be able to make it over the pass. We weren’t eating enough…so I reached for another potato or two.

Then he informed us that we could hire porters for the next day’s hike. The big one. Ten hours, summiting at 14,000 feet. If we wanted, he would arrange for porters to carry our bags. I’m not going to lie. I considered it. I asked him if I could make it and he said yes. He also said that there would be others coming back down the mountain tomorrow who wouldn’t. That he’d seen them and he knew who they were. When we asked how he knew, he said they had a different, “flavor†about them.

Then he told one of the guys in our group that he would have to hire a porter. And that it wouldn’t be a bad idea for one of the women, the one who was sick and coughing most of the time, to hire one as well. It was a blow. We could all feel it. Nobody wants to be told that they can’t make it on their own. But he was right.

By the end of the night, two porters had been hired. They’d be carrying two packs. They’d also be carrying the extra sleeping bag that I was carrying for LeAnna. We were traveling with one big bag and one smaller one, our gear consolidated. We’d planned to switch off, but I was holding up well, except for the blasted sleeping bag. It was rented from the trekking company and not designed to be light. I was glad to hand it over.

It was pitch black when we climbed into our tents. Each of us had our little headlamps lit for the brief time it took to crawl into the tents. And then it was black. Blissfully dark and quiet. The hard ground under us was lost as we drifted into sleep.

September 19, 2010 1 Comment