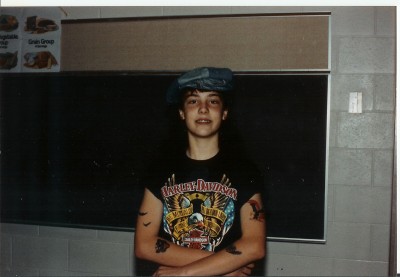

The history of biker hair

I think this was the year I decided to go for more of a grown-up Halloween costume. It might have been a bit of a miss.

I think maybe it’s the hat.

March 23, 2010 Comments Off on The history of biker hair

The history of hyper hair

Just for the record, that is a hypercolor shirt tucked into my fluorescent shorts.

And those are my braces. And some mighty fine shades.

March 22, 2010 Comments Off on The history of hyper hair

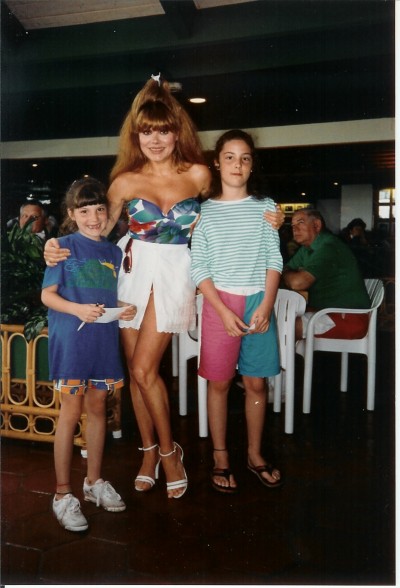

The history of Charo hair

On a vacation in Hawaii, my family went to Charo’s restaurant. Oh yeah, and she was there.

Those shorts are super-rad. Oh yeah.

March 20, 2010 Comments Off on The history of Charo hair

The history of skiing hair

This is sometime around 1983. This is what happens when you grow up a mile from a ski resort – in the 80s.

Those are my super-awesome K2 skiis. (I would later be known as K2 in my legal career.) For those of you who know my sister, that’s her in the red suit in the background. We were rad.

March 18, 2010 1 Comment

The marginalized masses

Okay, let’s review:

We commit emotional violence on each other all the time, like when we talk about neighbors or delegitimize people’s feelings.

We do it because we’re suffering from mass Post Traumatic Stress Disorder brought on from the emotional trauma we suffered in junior high and high school (and every day after that).

Which causes us to use power-structures to marginalize each other.

We find ourselves in a hierarchical system that requires us to rank ourselves in relationship to each other. What kind of car do we drive? How much education do we have? What kind of job do we do? We all know which cars are valued more than others, which jobs are respected more. If there’s any question, just watch an evening of tv and commercials.

Or we can look back at high school. I remember clearly the day someone came up to me and asked the question, “so are you a jock or a hic?â€Â Boom. There it was. I was stunned. I realized a couple of things in the seconds it took me to compose myself: 1. I don’t have a horse, but maybe I’m spending more time than I thought with the Rodeo crowd; 2. I get to define myself; 3. I better be careful how I answer this question.

I knew exactly where jocks fit in, as opposed to hics, as opposed to stoners, and punks and drill team, and student council and band. Even the loners, who refused to be part of a group had a label and a rank in the system.

In this system, those at the top have more power, more influence. In order for this to be true, the system requires there to be other people on the bottom. So, in order to stay in control, those on the top need to marginalize those on the bottom to keep them from gaining influence. To give them a label, and put them in their place.

I think I wore my letterman jacket every day for the rest of my high school career.

Here’s my background. For a number of years, I worked in the realm of GLBT politics. I worked first as a community organizer, a ground-level trainer, and then served in leadership positions on state and national boards.  I organized door-to-door canvasses, phone banks, community meetings and political rallies.  I sat in rooms with high-level operatives and I sat in rooms with disillusioned naysayers.

I learned a lot.

When all was said and done, I learned one thing in particular. Something that has informed the way I approach individuals and groups representing communities of individuals. Something that has informed the way I reach out to and react to others in both my political life, and in my personal.

We use systems of power to marginalize. We do it as individuals. And because organizations are made up of individuals, we do it organizationally, too.

Here’s how I started to see this in my life. The organization I worked for purported to represent a minority community. It was perhaps the best job I’ve ever had. I loved training people to talk face-to-face about their lives. I loved listening to community members who had ideas about how to best engage in a political and social movement. I loved planning rallies, and bringing people to see legislators. I loved making sure people felt heard.

I was a true believer. I believed deeply in the issues, and in the people I was representing. I believed in the power of people to affect the views of their neighbors by simply talking with them. I believed in the power of communities to affect the views of legislators by doing the same. I believed in my organization.

I watched as the organization I loved, an organization representing marginalized individuals, moved into a position of relative power. I worked hard to help make this happen. I watched as it gained relevance, found its voice, and developed friends in powerful positions.   Then I watched as the organization chose to use the precise system that had marginalized it and its members to isolate and marginalize others. I say “chose,” but it wasn’t something conscious.

It took me a little while to figure out what was happening and why. I was uncomfortable with the snide comments that would be made about fellow organizers – “competitor†groups representing the same community, and individuals with differing views. The categorical discounting of anyone who didn’t agree with the game plan developed by my organization. The unweilding push to isolate and discredit those who questioned.

So I volunteered to attend the “coalition†meetings of competitor groups, to engage those who had been discounted. To talk with the people I felt we should be representing, and not just those who could bring the organization the institutionalized power it was seeking.

As I did this, I heard the fear in the voices of those who felt they had no voice. I heard the anger of those who felt they had been shut out. And I saw a different path emerging.

The power structures that pedal influence, that require a hierarchy to function, assume that there’s a limited amount of power and influence available; that anyone who gains power, does it at the expense of another.

But we don’t live in a world where there is a finite amount of power. That’s not reality.

The reason we set up the systems that we do is that we’re stuck in a cycle. We’ve been hurt, we’ve been wounded, we’ve been discounted and marginalized and isolated by those who we saw as having power. And the second we find ourselves in a position of relative power, we do what we think we’re supposed to do when we’re in power. We hurt and wound and marginalize and isolate others. Because that’s the system we have been operating in.

But we don’t have to.

If we can take a step back, look at what we’re doing, and why we’re doing it, we’ll be able to find a new path.

Those of us who find ourselves marginalized at some point in our lives (and that’s all of us) can either work to put ourselves in a position of power, using the systems in place to marginalize others, or we can do something different. We can reject the system altogether. And that’s scary.

It means opening up. It means being available to hearing conflicting ideas and opinions. It means being vulnerable and engaging others with the imperfect language that we have, and the incomplete vocabulary of someone who is learning.  It means trusting that, by giving power to another, everyone’s power will increase. That by helping someone else to find their voice, all of our voices become clearer.

It means forgiving ourselves and others for the harm we’ve done and recognizing that it was done with a complete lack of awareness. It means committing ourselves to non-violence in our interactions with each other and ourselves.

And it means that we’ll have to stop ourselves, with great kindness, when we forget and fall back into the old patterns.

But it also means that we can move forward, intentionally, creating the relationships and the interactions that we want, unencumbered by our wounds. Doesn’t that sound really excellent?

March 17, 2010 3 Comments